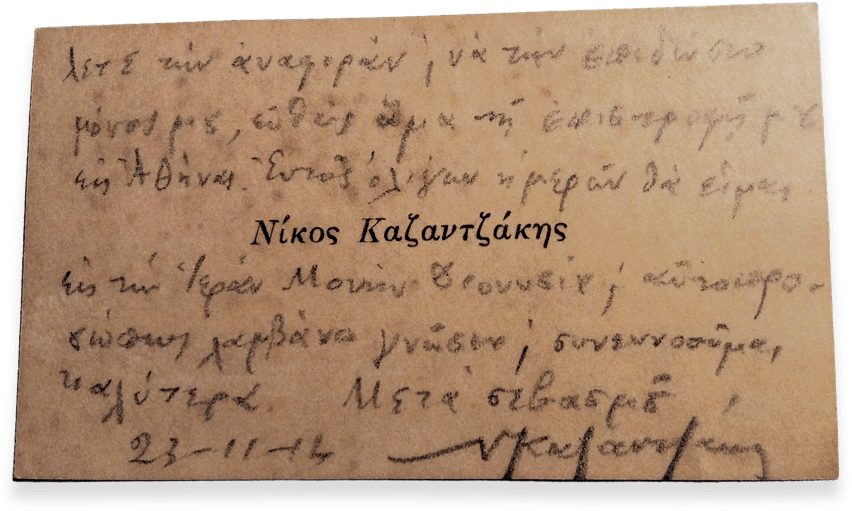

In November 1914, two of the greatest Greek writers, young friends at that

time, Nikos Kazantzakis and Aggelos Sikelianos, visited Mount Athos with a letter of recommendation from the

Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos.

Nikos Kazantzakis decided to take this trip when he saw a photo

album of Mount Athos at the house of Sikelianos.